Build Your Skills

Learn music theory Train your ears Track your tempoRead Now

Get the Newsletter

Categories

- | BeatMirror (10)

- | HearEQ (11)

- | Waay (23)

- | WaayFinder (1)

- Audio (16)

- For musicians (34)

- Guitar (2)

- Music theory (15)

- News (43)

- Startup stories (2)

- Tutorial (4)

Keep in Touch

About Ten Kettles

We love music, we love learning, and we love building brand new things. We are Ten Kettles.

Read more >-

November 30, 2022

Sound vs Music

Types of Sound

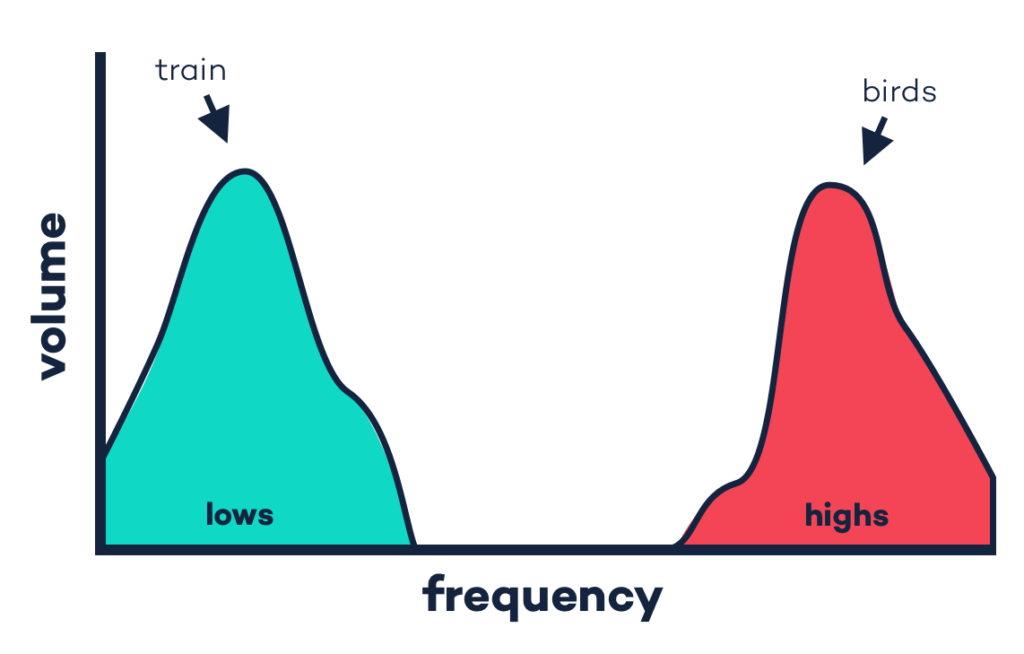

As humans, we hear a wide range of sounds. We hear very low noises, like the rumbling of a distant train. And we hear very high noises too, like a bird chirping outside the window. We say that the lower sounds are made up of lower frequencies and the higher sounds have higher frequencies. (More on that here.) Here’s what that looks like:

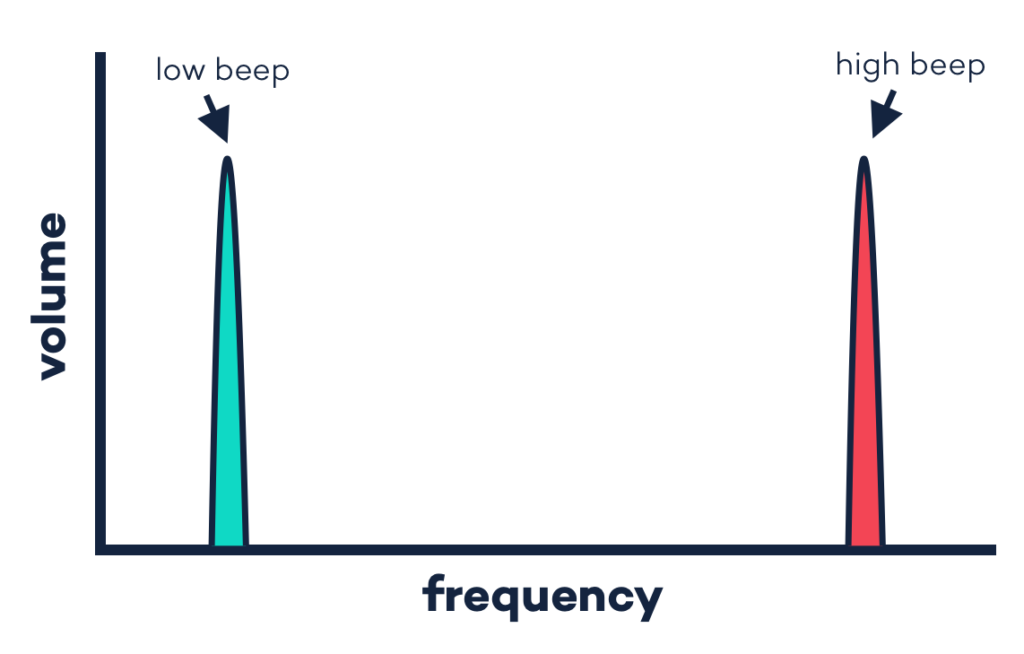

Now, sounds aren’t just low or high; they can be simple or complicated too. The simplest sound is basically a dialtone—a beep that goes on and on:

The sound you just heard has only one main frequency. So our frequency graph would show only one frequency too. If our sound was lower, the spike would be at a lower frequency (to the left). If it was higher, then the spike would be at a higher frequency (to the right).

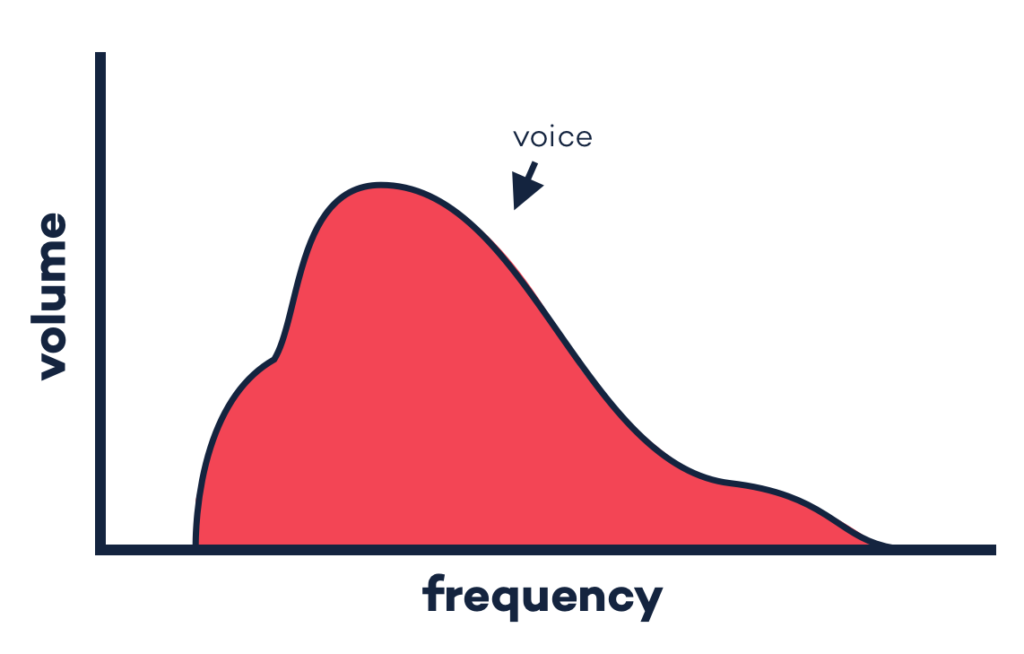

But not all sounds are simple. Many are complicated! For example, our voices are made up of many different frequencies. If we have a lower voice, those frequencies will be lower; if we have a higher voice, they will be higher. But in either case, there are a whole chunk of different frequencies in a complicated sound.

Which Sounds Are Musical?

Up to now, we’ve just talked about sound. But what about music?

Can any sounds—can any frequencies—be called music?

No, not really.*

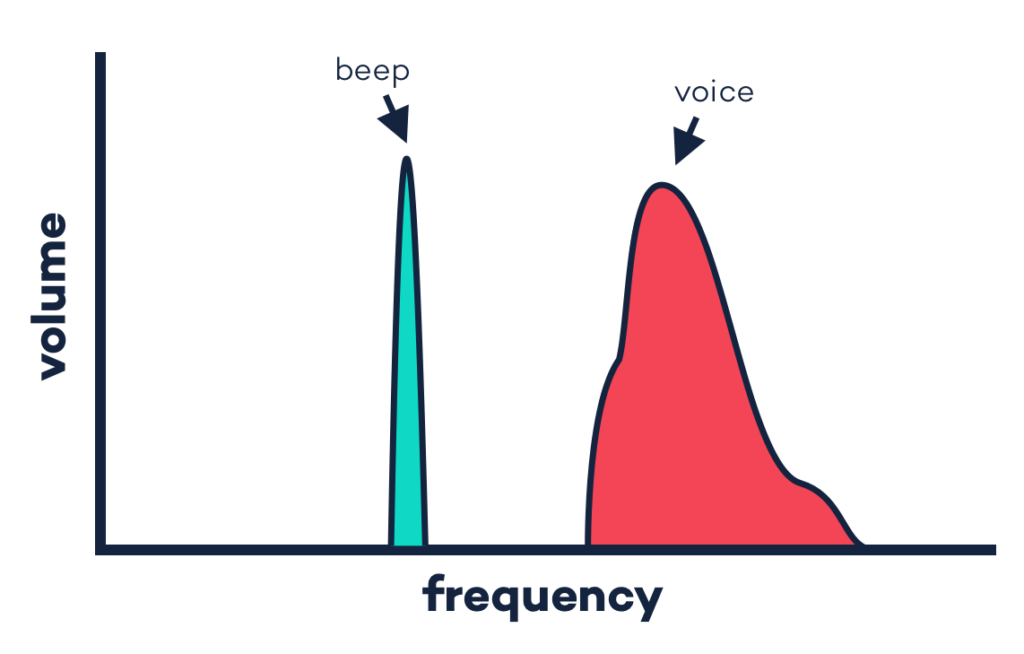

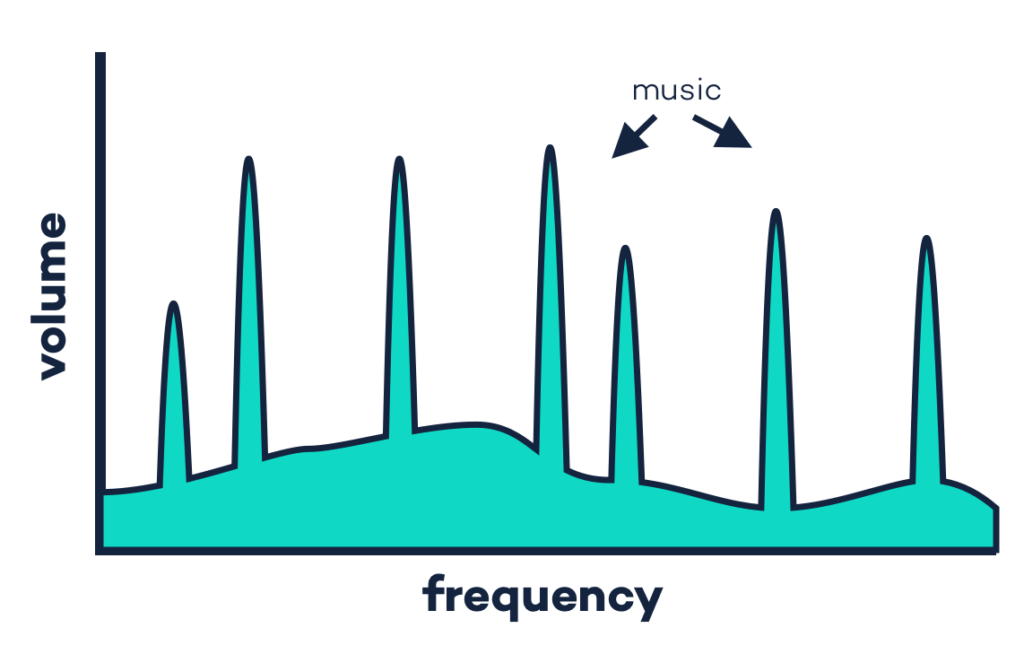

Let’s zoom into the frequency graph from above and compare a non-musical sound to music. The red frequencies could be from the non-musical sound of someone talking. The green frequencies are what a song might look like.

The non-musical sound has all sorts of frequencies in there—there’s no obvious pattern to it. But the music is different. It’s spiky! Just like our beeps! We can see music has those special “simple sounds” we talked about before… but what are they?

Those are notes!

Notes are simple sounds with one main frequency. Whether you’re singing them in the shower or playing them on a guitar, every note has one frequency that’s more important than all the rest.

So how many of these notes are there? This is where it really gets interesting. Across pretty much all the music you’ve ever listened to, there are just a handful. If you’re a Western reader (say from Canada, Europe, USA, New Zealand, etc.), the music you likely listen to has only twelve different notes. Let’s think about that for a moment. Every artist, every album, every song: just twelve different notes!

That’s bananas.

Across a whole song, the bassist is going to be playing—at most—twelve different notes. The singer is going to be singing, yup, at most twelve notes. The guitarist, keyboard player, bassoonist, everyone. (Well, except the drummer. Though very important, we probably wouldn’t call those percussive sounds notes.)

Notes and Keys

Remember how we said that the music we listen to has, at most, twelve notes? Well, there’s something very interesting about those twelve notes.

Like a group of twelve people, some notes “get along” pretty well. Put them side by side and they usually sound good! They’re friends. But others almost never get along. They just don’t sound good together.

Here’s an example of notes that “play well together”:

And here’s an example of notes that clash. Not friends at all:

Just like a group of people, it’s not so much that some notes are “good” or “bad.” It’s just that some combinations of them resonate a little better than others. Groups of notes that do play well together have a special name too: a key.

The melody above (the one that sounded good) had notes that belonged to the same key. And you could hear what that sounded like: it sounded pretty good! The second melody, the one that sounded awkward, had notes that didn’t belong to the same key. Not friends.

Most keys (i.e., groups of notes that sound good together) have just seven notes. That nice-sounding melody above came from a key that had the notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. Although it didn’t use all the notes, it could have, and those would have sounded good too. Here, I’ll prove it. Let’s add in all those notes so you can hear:

So even though a song could use all twelve notes, it’s often much simpler than that. Because many songs stick to just one key, they only use seven notes. Across the whole thing! It still blows my mind that with such a small set of tools, we’re able to experience such an enormous variety of music. It’s amazing.

Outro

We’ve covered lots of interesting topics in this article:

- Some sounds have just one main frequency; others are complicated and have a bunch.

- One type of simple sound is a musical note. There are just twelve of these notes!

- Some notes “play well” together; others don’t. We call a set of notes that “get along” a key.

If you like this article, then you’ll really like Waay. It’s our app for applied music theory—stuff you can take straight to your instrument and use. Waay uses bite-sized video lessons, interactive exercises, and memory retention tools to build your music theory skills from the ground up. It’s free-to-try and available for iPhone or iPad today!

*The sort of melodic music most of us are used to. A drum beat or skilled poetry reading can definitely be musical, but that’s not what we’re talking about here.

Comments